Surprise! Who knew Scott County had all these plants?

Leeward Solutions, LLC, has been featured in local coverage in Scott County, including this article by writer Alma Gaul in the Quad City Times, November 27, 2017. The article describes the roadside vegetation inventory of Scott County that was conducted for the Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management program. The article appears in the print edition, front page, with a different title. In addition, the North Scott Press published additional coverage by Mark Ridolfi.

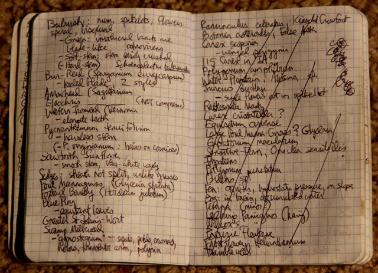

PLANT INVENTORIES

Botanical or floristic inventories have a wide variety of uses and about as many

methods of data collection and management. The choice of method depends on the

goal of the inventory.

A simple inventory list may be preferred, and the person conducting the inventory will need familiarity with nearly all the regional species that could appear across a number of ecosystems and plant communities.

Often the quality of a particular ecosystem, such as tallgrass prairie, is best demonstrated by "conservative" species, the plants that are most likely to suffer loss in abundance from disturbances. Often these are also less familiar species because they are not dominant in their plant community and/or because they are easily overlooked. A good field botanist needs to recognize these or, at the very least, be able to place an unidentified species in a larger taxonomic group and use botanical keys and laboratory equipment to complete the identification.

An inventory list typically includes the scientific name, common name(s), coefficient of conservatism (see below for explanation), endangered or threatened status, and actual or typical ecosystem occurrence.

Ideally, inventories should include at least three visits during different seasons. In the Midwest, many plants bloom according to a cool-season or warm-season "schedule." Cool-season plants appear in early to mid-spring and flower from late March to June. Seed production begins anytime from April to mid-summer. Some of these plants have almost no trace on the surface by June, because they die back to

dormancy.

In contrast, warm-season plants, including many well-known prairie species, may exist as green growth through early to mid-summer, with flowering occurring in late summer to autumn and seed production thereafter. For example, an April inventory may completely miss many warm-season forbs and grasses that have barely sprouted or grown shoots. It is necessary to recognize seedlings and young plants from their overall growth pattern ("aspect") and detailed botanical features.

This link to the Marion County Roadside Vegetation Species List takes you to a PDF file (Adobe Acrobat Reader required) that shows the species list for the roadsides in Marion County, Iowa's, secondary road system (paved, gravel, dirt surfaces). The list was produced under contract with Iowa Heartland Resource Conservation & Development, as part of a complete survey of roads in the county system.

A second link opens an inventory of a small roadside remnant in Boone County, Iowa, that was done on a pro bono basis. In addition, an article from the North Scott Press (opens in new browser window) describes a roadside vegetation survey in which Leeward provided primary field inventory services of Scott County's secondary roads.

Beyond listing, mapping of ecosystem remnants or restoration efforts may be a goal. Mapping enhances a project in which preservation and expansion of an existing area of native plants are desireable. If seed collection for restoration of other areas is one goal, good mapping can help the collectors with relocating a patch of a given species during peak seed production.

Statistical methods for assessing the species populations and quality of a plant community carry the analysis even further. These start with detailed inventories, plot-based studies of species populations (by ground coverage estimation or stem counts) and, in the best of worlds, GIS mapping. A Coefficient of Conservatism is assigned by species abundance and the Floristic Quality Index (FQI) is determined for the site.

For preservation and restoration work, a high-biodiversity setting is optimal. Such remnant areas are rare in Iowa and the Upper Midwest Corn Belt. More likely a remnant area has degraded over time so that only the most tolerant species are left, or

natives are well mixed with nonnative species. Interseeding and prescribed burning or mowing may work well to avoid disturbance of the existing native plants and encourage their regrowth.

If very few or no native species exist at the site, the process must start from scratch. It's best to use local ecotype seed that has been gathered from remnants within 50 to 100 miles and is already adapted to conditions at the restoration site. Otherwise, seed from a regional supplier is a last resort, in hopes that several years of management will result in a genetic base similar to the native local species.

Except for an area that already is a high-quality remnant, the change in the FQI or other numerical expression of quality over time is more important than a quality measure at one point in time. Restoration, whether through enhancement of an existing plant community or beginning from nothing, is a multi-year process that requires patience and monitoring.

Roadside plant inventories can add to our understanding of plant communities before European settlement. In this photo, a dense growth of sedge (genus Carex) occupies the ditch in the foreground, adjacent to a farmed prairie pothole that is partly bare from late spring water levels in 2019. The sedge is a potential seed source for wetland reconstruction.

O D von Engeln Preserve, Tompkins County, New York, holds a variety of ecosystems and glacial features, including this small bog.

The study of different ecosystems aids understanding of each system and its plant community. Above, desert conditions at Sabino Canyon, Tucson, Arizona, give rise to entirely different types of plants and plant adaptations to dry heat and very unpredictable rainfall.